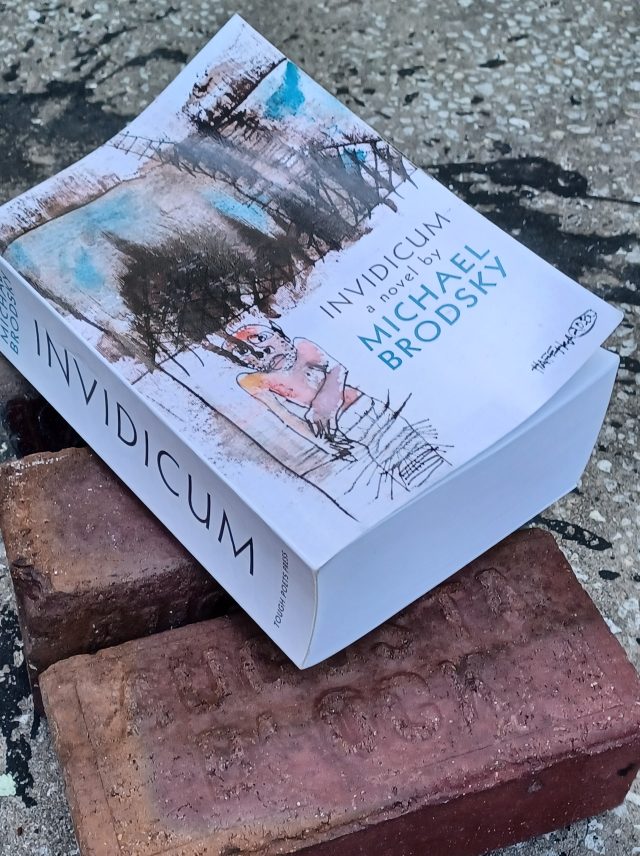

I am at a loss how to begin a “review” of Michael Brodsky’s astonishing opus Invidicum (published by Tough Poets Press and illustrated by the great Michael Hafftka), not only because I’ve never read anything like it (apart, that is, from other Brodsky novels), and not only because it is an Augusta Block of a book at nearly 1200 pages. But also because the author has made any attempt at a “review” (suddenly the word smells too bad even for parentheses) very difficult, if not suspect. The Derridean concept of the writing of a text—any text—being connected to the endless chain of writing from the distant past to murmurs around the globe has never been more evident than in this novel. My notes sprawl all over the place and it probably doesn’t matter where I start since such conventions as plot, timeline, character development, or even a pyramid of ideas—all thought-packets in Invidicum are of equal value—are thrown decisively out the window with a whiplash smile, as Billy Idol would say, so anything like a “synopsis” is unthinkable. Oh, and anyone who loves Brodsky’s work as much as I do (and have for decades and that ain’t nothing) should be chastened by the heaps of derision cast on fans; we are told repeatedly in the novel that they come and go while “detractors are forever.”

I have before encountered styles so powerful that they seem to overtake you when you pick up a pen to write your “own” words (more on the notion of writing your own words below). Brodsky’s style is a force—show me one more powerful—but he’s not the lion in the path of this “bump-on-a-blog” (Brodsky’s term, p 47). I can put on my big boy pants and write all by myself (and the nods to his style [see below] are deliberate; it seems to me another indication of what the novel does, the whole imitation being the sincerest form of flattery bit). I feel pulled rather toward a whirlpool of concerns and questions that I have no intention of answering, as if I could. I think the only way to honor Invidicum is to remain disturbed, and to leave every last refuge of comfort-seeking scoundrels out of it.

What follows will be a series of thought-packets (the term is Brodsky’s) in no particular order, none more important than the others and chosen for no other reason than they appealed to this reader. Every reader will choose their own packets. I read an article last week about book clubs that get together and discuss—for years—Finnegans Wake one page at a time. If humanity survives, Invidicum will become such a book. Ten people could write their own reviews of Invidicum and a reader unfamiliar with the novel might wonder if they were all talking about the same book (that could be another way to go about this—pose as ten different reviewers…). There are packets to keep readers busy for many years to come. Grab a drink and get comfortable. This is going to be a long one. If you came here looking for the CliffNotes version, sorry (well, not really) to disappoint you.

Packet One: What is it? Is it a novel?

The novel is the most fluid art form there is. The question is asked in the spirit of Jackson Pollock’s, “Is it a painting?” In a gesture that still opens eyes today, Pollock turned his back on the remaining fundamental conventions of painting, literally throwing the canvas on the floor and dancing over it with sticks of dripping paint. Canvas and paint were involved, and that’s about it. The question is like asking, is it a monster, or does it still work, and if so, how? It is easy to say in a few words: Invidicum is a novel told in a range of internal dialogues concerning a group of test subjects (named after historical figures or characters from literature) for an experimental drug called Invidicum to cure envy. After that, no conventions apply. And with apparent joy the author trounces conventions and introduces elements that would probably not be encouraged in a creative writing class, such as taunting the reader in various ways and challenging them to look up anything from words to movies to philosophical articles (and don’t hesitate to take up the challenge; I have found that my time has always been rewarded), a series of footnotes that serve an array of functions—ditto extensive parenthetical remarks—passages of social commentary that range from straight observation devoid of irony to vicious satire and right up to boiling outrage. The characters, such as they are, are often interchangeable, and someone, some thing, called “the Master” keeps making an entrance. Presumably it’s the author—or a reflection of the author function—but one of the exceptionally weird things about these acts of self-referentiality (if it is fair to call them that) is that, one by one, the “characters” all become conscious of the Master. Now, if that sounds like any novel you’ve ever read before, let me know. It may indeed be a monster. But does it work?

Yes, it does, and for many reasons (see below). But there are two big ones. The first, already mentioned, is Brodsky’s style. If writing, pure writing, can sustain your interest, this will do it. His wit is the sharpest I’ve ever encountered and whenever I’m in doubt about how to use the English language—just the basic shit about how to construct a sentence—I start reading a few pages of Brodsky (oh, sometimes I go to Henry James, but, please, if you see any weaknesses, the student takes full blame). As weird as the ride gets—and it gets very weird at times—Brodsky’s style, sure as a rock, carries you through.

The other reason it works is because of the richness of the packets. The questions are important and fascinating in themselves: the nature and function of envy in our culture, what does it mean to be a master of your discourse?, who is in charge of language?, and what does it mean to write fiction?, to name a few.

Finally (that is to clip off this packet so we can move on to another one), thinking about Pollock’s question seems to shift the question, “what is a painting?” toward engaging with the adventure of painting itself. Pollock not only made paintings (duh, it’s paint applied by a person to a surface for the purpose of a viewer’s meditation, just as a novel is making up a bunch of stuff in the form of prose for the purpose of sparking and challenging a reader’s mind), but he left behind artifacts that allow the viewer to engage in the adventure of painting, and not only allow them to but they must do it to engage with the way in which it is indeed a painting. The viewer must imagine what it must have been like to move with that paint. In imagination at least the viewer is painting. This is what Invidicum does for the novel. Because of all of the shifts of focus, because of all of the intrusions of the Master and reflections on the Master by Melanctha Herbert and the other characters, the reader is forced to shift focus: now you’re in the raft going down the rapids and—suddenly!—you’re floating above the scene. To read Invidicum is to be conscious of engaging in the adventure of reading from multiple perspectives. Far from sitting down and submitting to an evening’s entertainment, you are not even in a story but compelled, through shifts in pov, to consider your place vis-à-vis the text, and this, in turn, raises questions about the nature and functions of language itself.